Terrence Malick's Badlands Turns 50

The birth of a philosopher king.

“Little did I realise that what began in the alleys and back ways of this quiet town would end in the Badlands of Montana.”

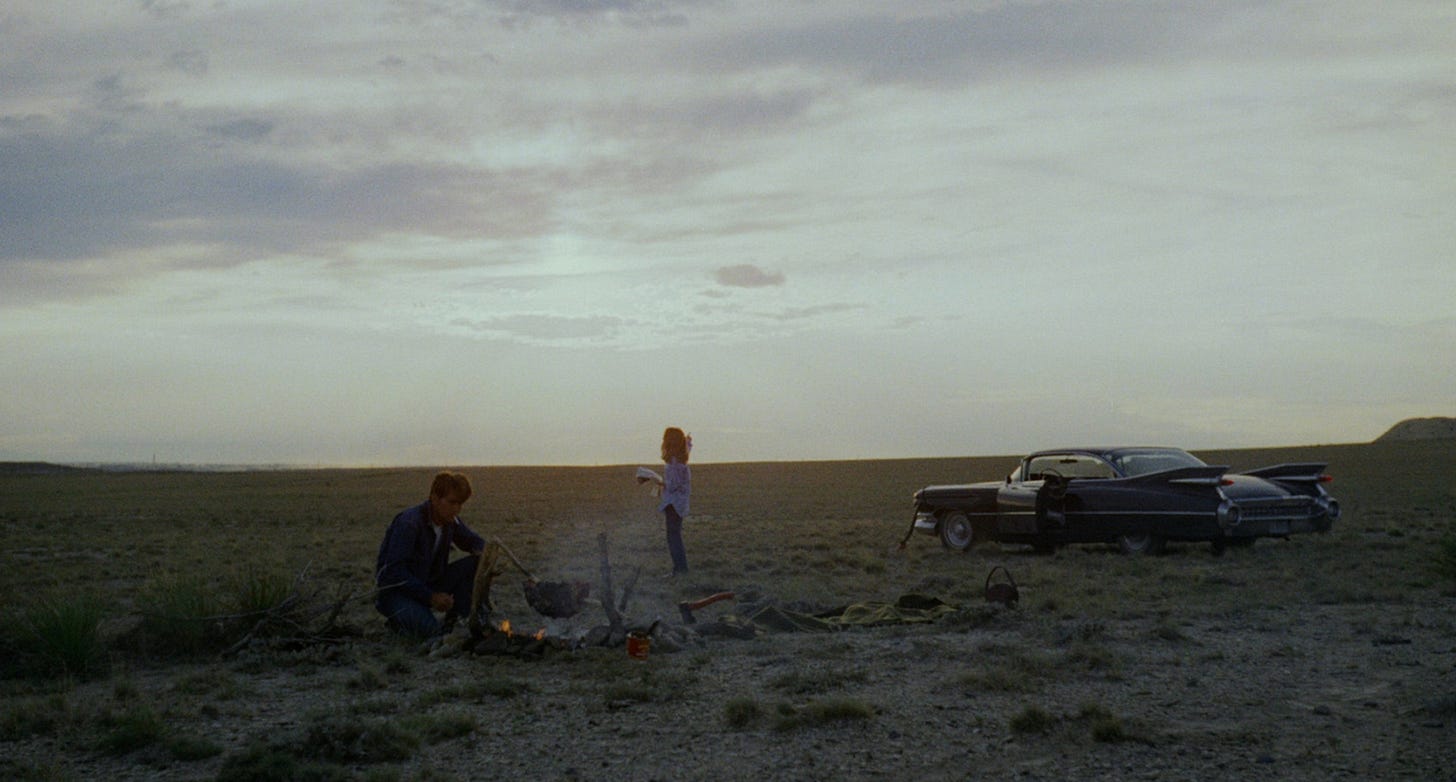

On this day, exactly 50 years ago, during the 11th edition of the New York Film Festival, a different kind of start was born. Terrence Malick made his feature film debut with Badlands. A tale of strange attraction between a twenty-something sociopath called Kit (Martin Sheen) and a reserved, introverted teenage creature called Holly (Sissy Spacek), who - quite nonchalantly - end up running away together and going on a serial killing spree in Montana.

It’s really Holly who watches Kit do the killing, while she narrates in a matter-of-fact cadance, her private, oddly poetic, thoughts. Thoughts like,

“It was better to live a week with someone who loved me for what I was, then years of loneliness.”

or,

“I sat in the car and read a map and spelled out entire sentences with my tongue on the roof of mouth where nobody could read them.”

and,

“I left Kit in the parlor and went for a stroll outside the house. The day was quiet and serene but I didn't notice, for I was deep in thought and not even thinking about how to slip off. The world was like a faraway planet to which I could never return. I thought what a fine place it was full of things that people can look into and enjoy.”

Beguiling, elegiac thoughts and words that have a way of sticking. Dancing on the fringes of philosophy, lightly scratching the great itch of the meaning of it all.

This ethereal narration is complimented by two sublimely subtle performances. Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, relative unknowns in 1973, went on to carve out iconic careers in Hollywood. But it was not their stars I referenced earlier. It’s the 30-year-old philosophy student-turned-filmmaker Terrence Malick who emerged onto the arthouse film scene and, in his own special way, created a new language of cinema.

Accompanying Holly’s soulful, intimate voice-over narration in Badlands, a trait that would go on to become a Malickian trademark, is the magistry of the American landscape and man’s rough congruence with the natural environment around him. And an attitude towards cruelty and violence that’s all the more chilling for how lackadaisical it is. I think of Kit casually stepping on the cow, and I shudder.

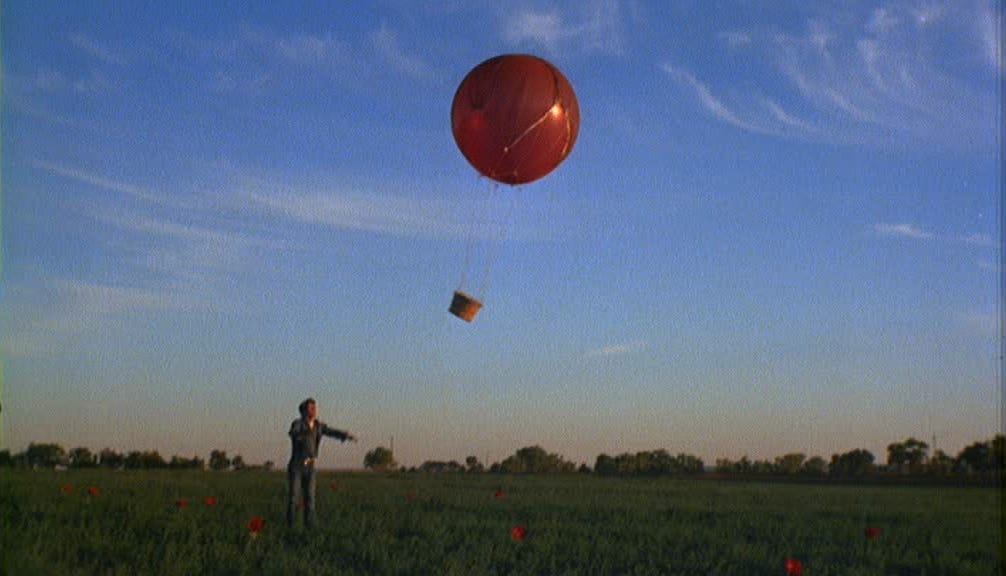

Malick’s signature magic hour shots - those in-between moments when it’s not quite day and not quite night - and his instincts when it comes to marrying imagery with music are all beautifully announced in Badlands. Carl Orff’s xylophones that would later be re-used in True Romance, and George Tipton’s German choral piece, add an unforgettably haunting layer to the story. Sprinkling it with fairy dust to give its fairytale quality and make it resonate all the stronger.

As far as debuts go, it doesn’t get more sophisticated, cinematically rich or mature, than Badlands. Most filmmakers who are well into their fifties can only dream of directing something as deeply moving and thoughtful.

In honor of its 50th anniversary, I watched Badlands again. I was transfixed as if for the very first time. Throughout my movie-watching life and brief shoulder-rubbing with film critics at film festivals, I’ve often seen, read or heard of “transcendental” cinema or “pure” cinema. I’ve fallen into the same hyperbolic rhetoric myself for certain reviews. But when it comes to Malick, it is no hyperbole.

Badlands is pure, transcendental and ever-so spiritual. It is a film that heralded a career - and a filmography - unlike any other. A career that is fifty years strong and a mere ten films heavy. Ten, with the force of thousands.

“You're quite an individual, Kit.”

“Think they'll take that into consideration?”