By the mid 1930s Pablo Picasso was already regarded as one of the greatest painters alive. In 1937, at the age of 55, he painted what became one of his career-defining masterpieces. The black-and-white masterpiece Guernica, depicting unforgettable stuff nightmares are made of, both human and animal, intertwined in a jagged, sharp, chaotic dance of death. It was the artist’s first explicitly political painting; a creative protest in response to the bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Picasso’s girlfriend and muse at the time, Dora Maar, was apparently a big influence1. She was a photographer and a very engaged left-wing, anti-fascist political activist.

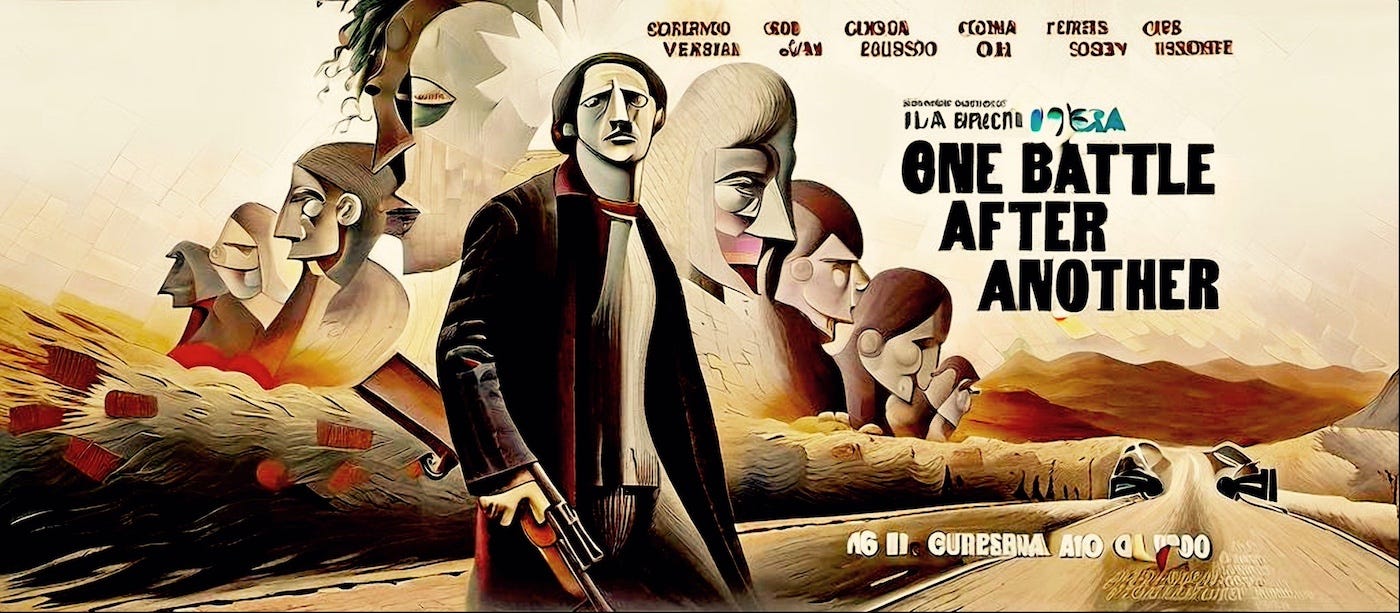

Flash forward to the mid 2020s, and Paul Thomas Anderson is rightly regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers alive. His latest film, One Battle After Another, is officially out in theatres and finds him, for the first time in his career, at the age of 55, at his most explicitly political. The periods covered in the film are left purposefully ambiguous, but it doesn’t take a PhD in Film Studies to connect the dots to America today. How much of the film is a creative protest to Trump 2.0 and the current crackdown on immigration that is sweeping the nation2, and how much of it is just PTA cracking his storytelling knuckles? Does Anderson have his own Dora Maar, a muse that inspired him to loosely adapt Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland into his own epic action-thriller centered around a chaotic group of anti-fascist activists? As the questions swirl, one thing is clear. One Battle After Another is a visceral piece of political art that makes a statement with the same blunt force trauma that I imagine Guernica carried when it was first unveiled, all those decades ago.

Anderson is even more direct in his approach that Picasso was - something which took me by surprise when I first saw the film, five days ago. Eschewing the delicacy of a paintbrush, Anderson opts to paint his strokes with a crowbar. It was hard for me to recognize the director who successfully balanced his themes and characters on a wire stretched across the full spectrum of the human condition in Magnolia (1999), or the sophisticated master of period filmmaking who peels the onion of romance down to its dark and beautiful center in Phantom Thread (2017). Even closest cousins Inherent Vice (2014) and Licorice Pizza (2021) feel like distant relatives despite similar uninhibited styles, because they’re wrapped in an elliptical allure that feels missing from the abrasive and abrupt One Battle After Another.

For his canvas, PTA chose a relic from the past - VistaVision. Similar to Picasso, who dug up archaic modes to paint Guernica as a monochromatic mural featuring mythical creatures, Anderson resurrects a dead format to create something purposefully anachronistic that demands our attention. “It’s so old, it’s new” as Marlene Dietrich says in Touch of Evil (1958). The fact that only four movie theatres in the whole world can actually project the film as it is intended to be seen makes it all the more precious and coveted. But marketing gimmicks are for mere mortals; PTA’s purpose with VistaVision is to use its expressive format as a way to accentuate his barstrokes.

The 1:50:1 aspect ratio makes the film feel condensed and compact, the symmetry of so many centered compositions is all the more prevalent in a square, driving the story perpetually forward as it steamrolls ahead. The deep colors, and that grainy, tactile texture our digital world hasn’t found a way to replicate just yet, adds to the feeling that we stumbled on a recently-unearthed 60s classic. I feel super lucky to be living close to London, one of three cities that can screen the film in its intended format. Needless to say, it looks and sounds in-fucking-credible in VistaVision. When I watched the film a second time, projected on standard widescreen digital, the difference was palpable.

The film is a bombastic, breathless escapade - unapologetically Guernica-esque in the starkly black-and-white way it carves the lines between the good guys and the bad guys with that crowbar. I can’t think of another film that pits Chaotic Good against Lawful Evil with such sharp contrast. We know exactly who we need to root for, there is no in-between, there is no gray, and there is no sliver of daylight between the creator and his left-wing activist creations, battling on screen.

While Guernica delivers its political message as buntly as One Battle After Another does, the painting is conceptually complex and symbolically ambiguous in ways that the film is not. That’s how it felt five days ago, at least. I’ve become too accustomed to the layered depths of PTA’s previous masterpieces, the intellectual mind-fucks and oblique cerebral experiences. With films like There Will Be Blood (2007) and The Master (2012) - cathedrals of cinema that resonate with profound meaning and eternal grandeur - Anderson set his own bar pretty damn high. And my tastes in film have been heliotropically-inclined towards auteurist, intellectually probing cinema, like a flower is to the sun, since a young age.

No wonder, then, that Anderson’s strikingly conventional approach in One Battle After Another stumped me at first. Critics like to use the word “accessible” just so they can avoid the dirtier synonym. For this is doubtlessly Paul Thomas Anderson at his most crowd-pleasingly…*gulp*…mainstream.

Plot in a Nutshell

A group of political revolutionaries engage in violent acts of resistance against the government until they break up. Sixteen years later, a Colonel with a personal vendetta seeks retribution by going after one of the group’s ex-members, now a deadbeat stoner, and his daughter.

When I saw the film for a second time, just yesterday, with the weight of expectation lifted, I realized something. The blunt force trauma Anderson’s assertive brushstrokes delivered in VistaVision made me dizzy to PTA’s signatures underneath the politics of the film. From Jonny Greenwood’s monumental, reverberant score (you only need to hear and feel it once to know it’s his best yet) to Sean Penn’s otherworldly performance as the grotesque Col. Steven Lockjaw - an instantly iconic villain destined for a spot in cinema’s all-time Rogue’s Gallery - everything feels designed to be imposing.

This includes the film’s breakneck pace, which hurtles forward with the kinetic energy of an escaped lunatic, frothing at the mouth in his straight jacket as he flees his asylum wardens. Editor Andy Jurgensen picks up right where he left off with the exhilarating ending of Licorice Pizza and let’s it rip. Cinema’s magical ability to freeze time is strong in this one; 2 hours and 40 minutes have never felt more like 1 hour.

Critics have showered the film in a hyper-rapturous orgasm of praise from the moment it had its World Premiere in Los Angeles a few weeks ago. “Greatest of the year!” “Decade!” “Century!” “All Time!” “Masterpiece!!” “Beyond a masterpiece!” And there’s no doubt I fell victim to expectation. Unable to escape the online euphoria, I allowed myself to wonder… could it be? Now that the aftershocks have settled, and I enjoyed it for what it was rather than what I wanted or expected it to be a second time around, I can confidently say that it’s not, but that’s not to say that there isn’t more than meets the eye.

There is enough brilliance in the film that not an hour has passed since I walked out of the Odeon Leicester Square theatre, five days ago, that I haven’t thought about it. I love the uncompromising bravado of the score and the performances. I love that it subverts the typical role of the lead, played by the mighty Leonardo DiCaprio at his most hysterical and baffled, to the point of making him a supporting player in his own movie. A lost man with all heart and no plan. I love Teyana Taylor’s performance as Perfidia, such a commanding presence in the first act that it hovers throughout the rest of the film, like a ghost haunting everyone’s every move. The climactic car chase, on an unforgettable road paved with more suspense than asphalt, is one of PTA’s most exhilarating, hypnotic sequences of his career. Cinema is rarely this pure nowadays.

What One Battle After Another lacks in intellectual heft, it makes up in undeniable entertainment value. Without a doubt the most hilarious and heart-racing of Anderson’s films. To quote Benicio Del Toro’s unforgettable, stoic Sensei Sergio, it’s heavy metal man. It’s also more emotional and poignant the second time around, Chase Infiniti’s performance as young Willa shines all the brighter. Beneath the surface, the film is about the bonds of parenting and especially the responsibilities of fatherhood - a signature PTA theme that trickles over from his greatest masterpieces - which transcends governments, revolutions and politics. Distilled down to its essence, it hits hard and deep. If there is a Dora Maar-type muse in PTA’s life that influenced him to make this movie, I strongly suspect it’s his own kids.

With Guernica, Pablo Picasso created his most public and accessible work at the age of 55. Off the beaten avant-garde path he’d been so well known and admired for, ending up somewhere more universal, with a highly charged political piece of art. With One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson created his most accessible work at the age of 55. Off the beaten auteurist path he’s been so well known and admired for, ending up somewhere more universal, with a highly charged political piece of art. Both men layer in a deeper message beneath the veneer of their respective creations; beneath Picasso’s Spanish Civil War and revulsion to bombing lies a deeper meditation on human suffering and myth of civilizational strength and order. Beneath the surface of Anderson’s portrait of a politically-charged and divided America lies a deeper allegory on parenting. Given that Picasso painted Guernica practically on the eve of World Word 2 as literal fascists ruled Europe, one can understand why his piece yearns for a world of order. On the other hand, Anderson’s One Battle After Another is made in a time when the word ‘fascist’ is thrown around too loosely, so he’s understandably more willing to embrace chaos over lawful order. As long as the heart is in the right place.

The parallels between these two artists and their two hybrid political artworks is uncanny, but time will tell how far it will truly hold. Will One Battle After Another end up being Anderson’s Guernica? The centerpiece of his oeuvre once all is said and done? It’s obviously way too early to tell, despite what some critics are saying. Given that Guernica was painted in the context of actual war and fascism, its cultural resonance as a profoundly moving anti-war symbol makes a lot of sense. It’s very sincere with its politics, because it had to be. I can’t see One Battle After Another reaching those lofty heights, given that the cultural context it was filmed in is largely defined by cynical rhetoric and not actual WW2-style totalitarian takeover. It’s much more satirical with its politics, because it can afford to be.

Paul Thomas Anderson is Picasso with a crowbar, disguising a love-letter to parenting and fatherhood in the form of a political thriller. The lack of a challenging narrative and the usual auteur-driven thematic depth we are accustomed to from him is definitely missing, but a second viewing of the film does beg the question: so, what? Does every piece of art have to be intellectually stimulating in order to resonate and reach great heights? Some stories don’t need to be told with a paintbrush. Sometimes, it’s best to just sit back, enjoy the ride, and embrace the chaos. And, if you have kids, be sure to give them a big hug next time you see them.

“She influenced Picasso to paint Guernica – he had never entered political painting before,” said Amar Singh, curator of a Dora Maar exhibition at the Amar Gallery. (Source: The Guardian)

Making good on his campaign promise, President Donald Trump has given Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers full reign to crack down on all illegal immigrants, and there are many credible reports that it’s getting nasty and out of control. For example. And another.

Your film reviews are always breathtaking. Now have to see this.